Brown’s Corner – PCL Padres, baseball at its best

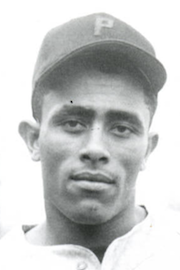

PCL Padres Tommy Helms and Lee May. Credit: San Diego Historical Society

Lane Field and Entrance. Credit: San Diego History Center

Lane Field and Entrance. Credit: San Diego History CenterBaseball means different things to different people, but it will long be remembered that Friday, August 12, 2022, was a dark day for the game, particularly in San Diego.

That was the day Major League Baseball announced the 80-game suspension of arguably its brightest new star, Fernando Tatis Jr. Like many star players over many years, it came after a failed drug test for use of Performance Enhancing Drugs (PED).

Like most that came before it, the suspended player almost invariably has a ready excuse – he unknowingly ingested an over-the-counter medication that just happened to contain some of the banned substance – just an honest mistake, right?

[wpedon id=”49075″ align=”right”]

Hardly! We’ve seen this act so many times in the modern era of chemistry and sport that we don’t want to hear or even pretend to believe it anymore. Athletes go to extraordinary physical and mental lengths to reach greatness. Increasing numbers cross the line into PEDs to improve performance, with few ever being caught, and there are rapidly falling records to prove it.

Baseball is one of many sports that should probably have its records divided into two categories; B-PED for before their emergence and A-PED for after their arrival and the damning influence on they have had on the sport.

America’s Pastime once meant something much more than it does today, and I can tell you what it meant to this baseball-loving kid growing up in San Diego in the 1950s.

On baseball season weekends, it meant staring at the grainy image shown on the screen of a 19-inch TV that only recently replaced a cabinet radio. If I adjusted the rabbit ears perfectly and tinkered with the tin foil just right, I could watch a major league ball game being described by Dizzy Dean and Pee Wee Reese.

It meant collecting soft drink bottles for the three-cent deposit I’d get back at Piggly Wiggly, knowing that finding two would fund the purchase of a nickel pack of Topps Baseball cards and slab of bubble gum. Best of all, I had a penny left over to go towards the next pack – any of which could turn up a Mickey Mantle card – but never did!

It meant hoping my dad or uncle would take me the next time they went to a game at Lane Field, and when that wasn’t in the cards, it meant a trip on the Number 2 bus for me. We lived at 26th and C Street, with the nearest stop just a block away on B Street.

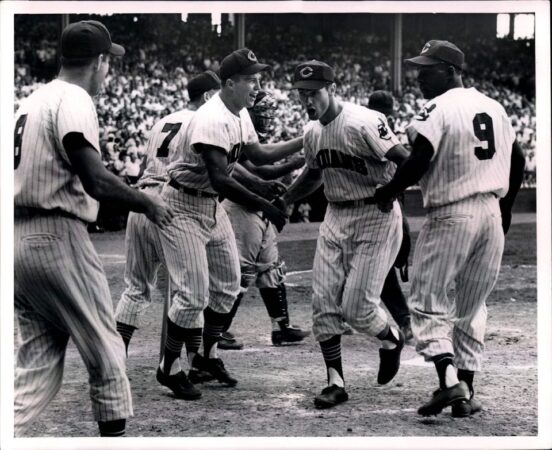

Buses replaced street cars I only vaguely remember, and both boasted the same route sign, one that read “2 Piers” and meant the end of the run. The piers, of course were those along the waterfront and just across Harbor Drive from Lane Field, home of my beloved San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League. As I recall, kids were automatically members of The Knothole Gang, and admission to the ballpark cost at most “two-bits,” as a quarter was known in those days.

The league’s quality of play was such that Major League Baseball designated the league as “open classification.” Once the Dodgers and Giants moved west in 1958, MLB demoted the PCL to AAA status.

PCL players were one stop from the Major Leagues, meaning a roster of the best young players aspiring to the next rung on the ladder, those falling from it, and on occasion established major leaguers on a rehab assignment or just needing to work out a few kinks in their game.

For many players, the league was the last stop on an escalator that led to the majors and the first stop leading away from them. There were some players who always seemed to be on it, and my favorite was Harry “Suitcase” Simpson. The common explanation at the time for the unusual moniker was the frequency that Simpson moved from league to league and team to team and was often told by broadcasters.

To my surprise, Simpson, who wore size 13 cleats, was given the name “Suitcase” by sportswriters who likened him to a big-footed cartoon character named Suitcase Simpson. Nonetheless, he lived up to the more common theory to explain his nickname by frequent moves, including being traded eight times in four years between 1955-59 and 17 times in 11 years in a career that spanned 19 seasons.

The Padres were an affiliate of the Cleveland Indians, Chicago White Sox, and later the Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies. The PCL was home to a number of teams up and down the western front, and I remember best the Hollywood Stars, Los Angeles Angels, Oakland Oaks, San Francisco Seals, Sacramento Solons, Portland Beavers, Seattle Rainiers, and Vancouver Mounties. My father and uncle were big fans, and my uncle, who owned the Newport Cleaners (a dry cleaning business rather than a current era PCL club) in Ocean Beach, had a customer who could arrange special tickets. They were special because aside from the normal screen that protected fans from foul balls, there was a sheet of clear plastic at most three feet by five directly behind home plate. He got those tickets for special games – and there were a few that stood out.

Cleveland Indians outfielder Rocky Colavito was touted as having the strongest throwing arm in the game. So, a special event was planned when he would attempt to span the 426-foot distance between the center field fence and home plate. Colavito threw three balls over the fence, the longest measuring 435 feet, 10 inches. Good thing he didn’t attempt the feat a few decades earlier when the distance was 480 feet.

Hank Aguirre pitched for the Padres, and few who were present likely forgot the time an opposing batter got to him for a critical home run. When it was manually posted in the centerfield scoreboard, Aguirre did something I’ve not seen before or since – he gave the scoreboard the finger.

Long-time baseball fans of advanced age like myself will recall the time Gil McDougal of the Yankees lined a drive up the middle that struck the Cleveland Indians ace pitcher, Herb Score, directly in the eye. In his first pitching assignment after rehab, Score was on the mound for the Padres, and it is safe to say he was never the same after going down from that line drive, as his ERA was nearly double what he‘d posted before the injury.

The seats with the clear view were not wasted when Jim “Mudcat” Grant was on the mound, and the pop of his fastball in the catcher’s mitt could be heard far and wide. If you were listening at home on the radio, that was a third strike call that radio announcer Al Schuss loved to make. Grant was something special, and it was not long before everyone in the majors knew it.

Minnie Minoso was a personal favorite, and in a bounce-back assignment from the majors, a young opposing pitcher decked him with an inside and head-high pitch that was called a ball. On the next pitch, Minoso swung wildly, and his bat helicoptered up the middle of the diamond, forcing the pitcher to leap up to avoid some hardwood to his shins. It happened a second time and then a third on pitches that Minoso had no intention of hitting, but he made his point.

Video replay in baseball has accomplished a few things. It allows teams to challenge an umpire’s call with the possibility of it being overturned on video replay. On the other hand, it has had an unintended consequence that removed some of the brightest color from the game – when players or managers argue an umpire’s call until thrown out of the game.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10/3e/103ec511-33e1-4ec6-a6b0-2b880bf2e35a/may2020_b35_prologue.jpg)

When it comes to vehemence in arguments, my favorite was Padres manager George Metkovich who loved an argument as much as I love warm peach cobbler with a scoop of vanilla ice cream. Metkovich would storm from the dugout or third base coaching box with fire in his eyes, screaming and stomping his feet. This would be followed by vigorous nodding of his head. In due time, the nodding would increase until his cap flew off his head – and this was invariably when the ump would give him the old heave-ho. This, of course, only enraged the Metkovich further. Still fuming and with arms flailing, he’d slowly make the walk of shame back to the clubhouse.

Speaking of umpires, my uncle’s favorite of all time was Emmet Ashford, who, in addition to being one of the most colorful and animated umpires baseball has seen, became the first black umpire to reach the major leagues. If his assignment was first base, at the start of the game, he’d sprint from home plate to first base as fast as he could – and certainly faster than some of the players. Ashford made every move and call with a flourish, including how he dusted off home plate.

Those were the best days of baseball for me, and I imagine many others. If there was concern about player behavior, it was that they were caught out too late chasing the bottle, the ladies, or both – and it was beginning to show in their performance on the field.

Jim has a long history in San Diego and is a rare native. A graduate of SDSU, but before the U was added, his first by-line appeared in the San Diego Union’s Sports Section in September of 1963, when he was the 16-year-old Sports Editor of The Russ, San Diego High’s school newspaper. He began writing outdoors features for the Evening Tribune in the 1970s and served as The Tribune’s outdoor writer from 1980 until its merger with the San Diego Union in 1990. As a freelancer, his outdoor stories have appeared in regional as well as national publications over many years. As an adjunct professor at SDSU and the former United States International University, he has taught a wide range of courses in the field of recreation.